How I Turned My Degree Upgrade into a Tax-Smart Move

Upgrading my degree was one of the best career decisions I ever made—but I almost missed a huge financial opportunity. It wasn’t until I dug into tax compliance that I realized I could turn tuition into savings. This isn’t about loopholes or risky moves. It’s about smart, legal strategies that actually work. Let me walk you through how I turned education expenses into a financial advantage—without breaking a single rule. What started as a personal journey to advance my career quickly evolved into a lesson in financial awareness. I learned that education, when paired with thoughtful tax planning, isn’t just an investment in knowledge—it’s a structured path toward long-term financial resilience. And the best part? You don’t need an accounting degree to make it work.

Why Going Back to School Costs More Than Tuition

When most people think about the cost of returning to school, they focus on tuition—the number listed on the university website or quoted during enrollment. But the true financial burden extends far beyond that single line item. For working adults pursuing a degree upgrade, the full cost includes not only tuition but also textbooks, technology upgrades, commuting or relocation expenses, childcare adjustments, and often, a reduction in work hours or even temporary leave from employment. These indirect costs can accumulate quickly, sometimes matching or even exceeding the price of tuition itself, especially when pursued part-time while balancing family and work responsibilities.

Consider the reality: a professional enrolling in an evening MBA program may need to purchase a new laptop, pay for parking or public transit, and adjust family schedules to accommodate late-night study sessions. Over time, these expenses create a hidden financial strain that many fail to anticipate. What makes this particularly challenging is that traditional financial aid packages—such as federal loans or grants—are typically designed for full-time students and may not fully cover the needs of working adults. As a result, individuals often end up paying a significant portion of these costs out of pocket, drawing from savings or increasing household debt.

This broader financial picture underscores why strategic planning is essential. Without it, even a well-intentioned pursuit of education can lead to budget shortfalls, delayed financial goals, or increased stress at home. The good news is that many of these expenses, when properly documented and aligned with tax regulations, can be leveraged to reduce tax liability. But this requires awareness and preparation. Viewing education solely as an expense ignores its dual role as a tax-advantaged investment. By understanding the full scope of costs, individuals can better plan for both immediate affordability and long-term financial benefit, especially when tax incentives are factored into the equation from the start.

The Tax Perks Nobody Talks About (But Should)

Despite the existence of valuable tax benefits for education, a surprising number of taxpayers remain unaware they qualify. According to data from the Internal Revenue Service, millions of eligible individuals fail to claim education-related tax credits each year, leaving money unclaimed on the table. These benefits are not hidden in obscure regulations—they are established provisions within the U.S. tax code, designed to encourage lifelong learning and workforce development. The most notable among them are the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) and the Lifetime Learning Credit (LLC), both of which allow taxpayers to reduce their federal tax bill dollar-for-dollar based on qualified education expenses.

The American Opportunity Tax Credit covers up to $2,500 per eligible student for the first four years of post-secondary education. It applies to tuition, fees, and required course materials, and is partially refundable—meaning that even if you owe no taxes, you may still receive up to $1,000 as a refund. This credit is particularly beneficial for those upgrading their degrees, provided they haven’t already completed four years of higher education. On the other hand, the Lifetime Learning Credit offers up to $2,000 per tax return, with no limit on the number of years it can be claimed. While it is not refundable, it applies to a wider range of educational activities, including graduate courses, professional certification programs, and part-time enrollment, making it highly relevant for adult learners.

Additionally, the Tuition and Fees Deduction—though temporarily expired for 2023 unless extended by Congress—has historically allowed taxpayers to reduce their taxable income by up to $4,000 based on qualifying education expenses. Even when not available, its past inclusion highlights the government’s ongoing recognition of education as a financially supported endeavor. Beyond these direct benefits, certain employer-sponsored educational assistance programs can provide tax-free reimbursement of up to $5,250 per year under Section 127 of the tax code. When combined, these tools create a powerful framework for reducing the net cost of education. The key is awareness: knowing what’s available, understanding eligibility, and integrating these benefits into personal financial planning. Tax compliance, in this context, becomes not just a legal obligation but a strategic opportunity.

Claiming Education Credits the Right Way

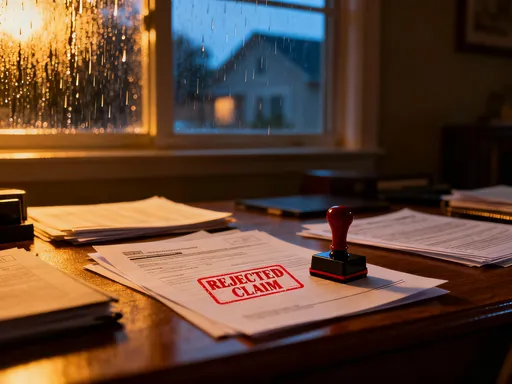

Claiming education tax credits correctly is critical to avoiding delays, denials, or even audits. One of the most common mistakes is confusing the American Opportunity Tax Credit with the Lifetime Learning Credit and attempting to claim both in the same year. The IRS does not allow double-dipping—only one credit can be claimed per student per tax year. Choosing the wrong one can result in a reduced benefit or a rejected return. Another frequent error involves miscalculating qualified expenses. Not all education-related spending counts: room and board, transportation, and personal expenses are excluded. Only tuition, mandatory fees, and required course materials purchased from the institution qualify under the AOTC, for example.

Proper documentation is the foundation of a successful claim. Taxpayers must retain official statements from their educational institutions, such as Form 1098-T, which reports eligible tuition payments. While this form is helpful, it’s not always required to claim the credit—especially if the institution didn’t issue one—but having detailed records of payments made, including dates and amounts, is essential. Additionally, the timing of payments matters: expenses paid in January for a spring semester beginning in the same year can be claimed on that year’s return, even if the course hasn’t started yet. This timing rule allows for strategic planning, such as prepaying tuition to maximize credit eligibility in a high-income year.

Another often-overlooked aspect is the income phase-out threshold. Both the AOTC and LLC begin to reduce benefits for taxpayers with modified adjusted gross incomes above certain levels—$80,000 for single filers and $160,000 for joint filers in the case of the AOTC. Those near these thresholds may need to adjust their financial strategy, such as shifting income or coordinating claims with a spouse, to remain eligible. Dependents also affect eligibility: if a student is claimed as a dependent on another’s return, only the taxpayer who claims them can apply for the credit. Navigating these rules requires attention to detail, but doing so ensures full compliance and maximum benefit. When filed accurately, these credits are a legitimate and powerful way to lower tax liability while supporting educational advancement.

When Employer Tuition Support Meets Tax Rules

Many employers offer tuition reimbursement programs as part of their professional development benefits, but not all of this support is tax-free. Under IRS rules, up to $5,250 in employer-provided educational assistance can be excluded from an employee’s taxable income each year. This includes payments for tuition, fees, books, supplies, and even certain required equipment. Any amount exceeding this threshold is treated as taxable compensation, subject to federal and state income taxes, as well as payroll taxes. For employees, this means that while employer support significantly reduces out-of-pocket costs, it can also complicate tax reporting if not managed properly.

The structure of the reimbursement program matters. Some employers pay the school directly, which simplifies tracking and ensures funds are used for qualified purposes. Others reimburse employees after they submit receipts, which places the burden of documentation on the individual. In either case, employees must ensure that their employer’s plan complies with Section 127 of the tax code, which requires that the program be nondiscriminatory and primarily benefit employees rather than shareholders or owners. If the plan meets these criteria, the tax exclusion applies. However, if the coursework is not job-related or is considered part of a required degree for a new profession, the exclusion may not apply, and the entire amount could be taxable.

Coordination between personal tax filing and employer reporting is essential. Employees should receive a Form W-2 with any taxable portion of reimbursement reported in Box 1. They should verify this amount and ensure it aligns with their own records. At the same time, they can still claim education tax credits for expenses not covered by reimbursement, as long as they meet eligibility requirements. For example, if an employer pays $4,000 toward tuition, the employee may use out-of-pocket payments for remaining fees to claim the AOTC or LLC. This layered approach—combining employer support with personal tax benefits—can dramatically reduce the net cost of education. Clear communication with HR, careful record-keeping, and alignment with tax professionals help ensure that employees maximize benefits while staying fully compliant.

Tracking Expenses Like a Pro (Without Losing Your Mind)

Accurate expense tracking is the backbone of any successful tax claim, yet many people approach it reactively—gathering receipts at the last minute or relying on memory. This approach increases the risk of missed deductions, incomplete records, or disallowed claims. A better strategy is to build a simple, sustainable system at the start of the academic year. The goal isn’t perfection—it’s consistency. By organizing documents as they come in, taxpayers can avoid the year-end scramble and ensure they have everything needed to support their claims.

A practical method begins with creating a dedicated folder—either physical or digital—for all education-related documents. This includes copies of Form 1098-T, tuition invoices, receipts for books and supplies, payment confirmations, and any correspondence with the school or employer. Digital tools such as cloud storage apps or personal finance software can automate much of this process. For example, using a smartphone to photograph receipts immediately after purchase ensures they’re preserved before they’re lost. Many banking and credit card apps also allow users to tag transactions, making it easy to filter and export education-related spending at tax time.

Equally important is maintaining a log of expenses, even if brief. A simple spreadsheet with columns for date, vendor, purpose, amount, and payment method takes minutes to update but provides invaluable clarity during tax preparation. This log can also help identify patterns, such as recurring fees or unexpected costs, allowing for better budgeting in future terms. Some taxpayers find it helpful to set calendar reminders at key points—such as the end of each semester or before tax season—to review and back up their records. The system doesn’t need to be elaborate; it just needs to be reliable. Being audit-ready doesn’t require perfection—it requires preparation. When documentation is organized and accessible, claiming education benefits becomes not only easier but more confident and stress-free.

Avoiding Red Flags That Trigger IRS Attention

The IRS uses sophisticated data-matching systems to verify the accuracy of tax returns, and education claims are no exception. Schools report tuition payments and enrollment status to the IRS via Form 1098-T, and employers report taxable educational assistance on Form W-2. When a taxpayer claims a credit or deduction that doesn’t align with these third-party reports, it can trigger an automated review or audit. While not all discrepancies lead to penalties, they can delay refunds and create unnecessary stress. Understanding what raises red flags—and how to avoid them—is crucial for maintaining compliance and peace of mind.

One of the most common triggers is claiming expenses that exceed the amount reported on Form 1098-T without proper explanation. While taxpayers can claim expenses paid directly—such as out-of-pocket book purchases—even if they’re not on the form, they must be able to substantiate them. Another red flag is claiming credits for ineligible institutions or programs. The school must be an eligible educational institution—generally, any accredited college, university, or vocational school that participates in federal student aid programs. Courses taken for personal interest, such as recreational classes, do not qualify. Similarly, claiming the American Opportunity Tax Credit for a student who has already completed four years of post-secondary education will likely result in disallowance.

Inflating expenses or claiming credits for dependents who are not actually enrolled can also attract scrutiny. The IRS cross-references enrollment data and may request proof of attendance or course completion. Additionally, claiming both an employer reimbursement and a credit for the same expense—known as “double benefit”—is prohibited. For example, if an employer paid $3,000 toward tuition and the employee claims a credit based on that same $3,000, it constitutes an improper claim. The safest approach is to apply credits only to out-of-pocket costs not covered by tax-free assistance. By maintaining clean, consistent records and aligning claims with reported data, taxpayers can avoid unnecessary attention and ensure their filings are both accurate and defensible.

Building a Smarter Financial Mindset Around Education

Ultimately, pursuing a degree upgrade should be viewed not as a standalone expense but as a strategic financial decision with long-term implications. Like any investment, its value is measured not just by immediate outcomes but by cumulative benefits over time. Higher education often leads to increased earning potential, greater job stability, and expanded career opportunities—all of which contribute to stronger household finances. When combined with disciplined tax planning, the return on investment becomes even more pronounced. Every dollar saved through legitimate tax credits or deductions effectively reduces the net cost of education, accelerating the path to financial payoff.

This mindset shift—from seeing education as a cost to recognizing it as a leveraged asset—transforms how individuals approach lifelong learning. It encourages proactive planning, informed decision-making, and integration of financial tools into personal development goals. Just as homeowners build equity over time, learners can build financial resilience by aligning educational pursuits with tax-efficient strategies. The habits developed in the process—such as careful record-keeping, awareness of eligibility rules, and coordination between employment and tax planning—extend beyond a single tax year. They become part of a broader financial discipline that supports budgeting, saving, and wealth accumulation in other areas of life.

For working adults, especially those managing family responsibilities, this approach offers a sense of control and confidence. It replaces financial anxiety with empowerment, turning a major life decision into a structured, manageable journey. The lessons learned go beyond the classroom: they include understanding how systems work, how to advocate for oneself, and how to make informed choices that align with long-term goals. In this way, the pursuit of knowledge becomes inseparable from the pursuit of financial well-being. Smart learners don’t just gain expertise—they gain leverage. And in today’s economy, that combination is one of the most valuable assets anyone can build.